Estonia

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (Retd.) |

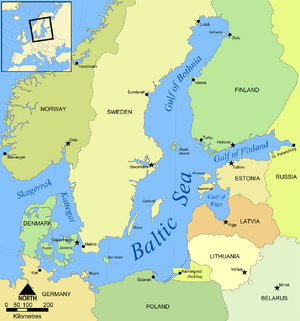

Estonia (एस्टोनिया) is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe.

Variants

- Estonia (/ɛsˈtoʊniə/ ess-TOH-nee-ə,

- Estonian: Eesti [ˈeːsʲti]

- Aesti - a people first mentioned by Ancient Roman historian Tacitus around 98 AD.

- Eistland

- Hestia or Estia (Saxo Grammaticus in his work Gesta Danorum)

Jat Gotras Namesake

Location

It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Lake Peipus and Russia. The territory of Estonia consists of the mainland, the larger islands of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa, and over 2,200 other islands and islets on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea,[1] covering a total area of 45,339 square kilometres. The capital city Tallinn and Tartu are the two largest urban areas of the country.

Estonian language

The Estonian language is the indigenous and the official language of Estonia; it is the first language of the majority of its population, as well as the world's second most spoken Finnic language.

Name

The name Estonia (Estonian: Eesti [ˈeːsʲti]) has been connected to Aesti, a people first mentioned by Ancient Roman historian Tacitus around 98 AD. Some modern historians believe he was referring to Balts (i.e. not the Finnic-speaking ancestors of Estonians), while others have proposed that the name then applied to the whole eastern Baltic Sea region.[2] Scandinavian sagas and Viking runestones[3] referring to Eistland are the earliest known sources that definitely use the name in its modern geographic meaning.[4] From Old Norse the toponym spread to other Germanic vernaculars and reached literary Latin by the end of 12th century when historian Saxo Grammaticus in his work Gesta Danorum referred to the area of what is now Estonia as Hestia or Estia, and its people as Estonum. The Livonian Chronicle of Henry (written ca. 1229) also used the name Estonia for the same area.[5][6]

History

The land of what is now modern Estonia has been inhabited by Homo sapiens since at least 9,000 BC. The medieval indigenous population of Estonia was one of the last pagan civilisations in Europe to adopt Christianity following the Papal-sanctioned Livonian Crusade in the 13th century.[7]

After centuries of successive rule by the Teutonic Order, Denmark, Sweden, and the Russian Empire, a distinct Estonian national identity began to emerge in the mid-19th century.

Prehistory and Viking Age

Human settlement in Estonia became possible 13,000–11,000 years ago, when the ice from the last glacial era melted. The oldest known settlement in Estonia is the Pulli settlement, which was on the banks of Pärnu river, near Sindi, in southwest Estonia. According to radiocarbon dating, it was settled around 11,000 years ago.[8]

The earliest human habitation during the Mesolithic period is connected to the Kunda culture. At that time the country was covered with forests, and people lived in semi-nomadic communities near bodies of water. Subsistence activities consisted of hunting, gathering and fishing.[9]

Around 4900 BC, ceramics appear of the neolithic period, known as Narva culture.[10]

Starting from around 3200 BC the Corded Ware culture appeared; this included new activities like primitive agriculture and animal husbandry.[11]

The Bronze Age started around 1800 BC, and saw the establishment of the first hill fort settlements.[12]

A transition from hunter-fisher subsistence to single-farm-based settlement started around 1000 BC, and was complete by the beginning of the Iron Age around 500 BC.[13][14]The large amount of bronze objects indicate the existence of active communication with Scandinavian and Germanic tribes.[15]

The middle Iron Age produced threats appearing from different directions. Several Scandinavian sagas referred to major confrontations with Estonians, notably when in the early 7th century "Estonian Vikings" defeated and killed Ingvar, the King of Swedes.[16] Similar threats appeared to the east, where East Slavic principalities were expanding westward.

In ca 1030 the troops of Kievan Rus led by Yaroslav the Wise defeated Estonians and established a fort in modern-day Tartu. This foothold may have lasted until ca 1061 when an Estonian tribe, the Sosols, destroyed it, followed by their raid on Pskov.[17][18][19][20]

Around the 11th century, the Scandinavian Viking era around the Baltic Sea was succeeded by the Baltic Viking era, with seaborne raids by Curonians and by Estonians from the island of Saaremaa, known as Oeselians. In 1187 Estonians (Oeselians), Curonians or/and Karelians sacked Sigtuna, which was a major city of Sweden at the time.[21][22]

Estonia could be divided into two main cultural areas. The coastal areas of Northern and Western Estonia had close overseas contacts with Scandinavia and Finland, while inland Southern Estonia had more contacts with Balts and Pskov.[23]

The landscape of Ancient Estonia featured numerous hillforts.[24] Prehistoric or medieval harbour sites have been found on the coast of Saaremaa.[25] Estonia also has a number of graves from the Viking Age, both individual and collective, with weapons and jewellery including types found commonly throughout Northern Europe and Scandinavia.[26][27]

In the early centuries AD, political and administrative subdivisions began to emerge in Estonia. Two larger subdivisions appeared: the parish (Estonian: kihelkond) and the county (Estonian: maakond), which consisted of multiple parishes. A parish was led by elders and centered on a hill fort; in some rare cases a parish had multiple forts. By the 13th century, Estonia consisted of eight major counties: Harjumaa, Järvamaa, Läänemaa, Revala, Saaremaa, Sakala, Ugandi, and Virumaa; and six minor, single-parish counties: Alempois, Jogentagana, Mõhu, Nurmekund, Soopoolitse, and Vaiga. Counties were independent entities and engaged only in a loose cooperation against foreign threats.[28][29]

Little is known of medieval Estonians' spiritual and religious practices before Christianization. The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia mentions Tharapita as the superior deity of the then inhabitants of Saaremaa (Oeselians). There is some historical evidence about sacred groves, especially groves of oak trees, having served as places of "pagan" worship.[30][31]

Crusades and the Catholic Era

In 1199, Pope Innocent III declared a crusade to "defend the Christians of Livonia".[32] Fighting reached Estonia in 1206, when Danish King Valdemar II unsuccessfully invaded Saaremaa. The German Livonian Brothers of the Sword, who had previously subjugated Livonians, Latgalians, and Selonians, started campaigning against the Estonians in 1208, and over next few years both sides made numerous raids and counter-raids. A major leader of the Estonian resistance was Lembitu, an elder of Sakala County, but in 1217 the Estonians suffered a significant defeat in the Battle of St. Matthew's Day, where Lembitu was killed. In 1219, Valdemar II landed at Lindanise, defeated the Estonians in the Battle of Lyndanisse, and started conquering Northern Estonia.[33][34] The next year, Sweden invaded Western Estonia, but were repelled by the Oeselians. In 1223, a major revolt ejected the Germans and Danes from the whole of Estonia, except Reval, but the crusaders soon resumed their offensive, and in 1227, Saaremaa was the last maakond (county) to surrender.[35][36]

After the crusade, the territory of present-day Southern Estonia and Latvia was named Terra Mariana, but later it became known simply as Livonia.[37] Northern Estonia became the Danish Duchy of Estonia, while the rest was divided between the Sword Brothers and prince-bishoprics of Dorpat and Ösel–Wiek. In 1236, after suffering a major defeat, the Sword Brothers merged into the Teutonic Order becoming the Livonian Order.[38] In the next decades there were several uprisings against the Teutonic rulers in Saaremaa. In 1343, a major rebellion started, known as the St. George's Night Uprising, encompassing the whole area of northern Estonia and Saaremaa. The Teutonic Order finished suppressing the rebellion in 1345, and the next year the Danish king sold his possessions in Estonia to the Order.[39][40] The unsuccessful rebellion led to a consolidation of power for the upper-class German minority.[41] For the subsequent centuries Low German remained the language of the ruling elite in both Estonian cities and the countryside.[42]

Reval (Tallinn), the capital of Danish Estonia founded on the site of Lindanise, adopted the Lübeck law and received full town rights in 1248.[43]The Hanseatic League controlled trade on the Baltic Sea, and overall the four largest towns in Estonia became members: Reval, Dorpat (Tartu), Pernau (Pärnu), and Fellin (Viljandi). Reval acted as a trade intermediary between Novgorod and western Hanseatic cities, while Dorpat filled the same role with Pskov. Many artisans' and merchants guilds were formed during the period.[44] Protected by their stone walls and membership in the Hansa, prosperous cities like Reval and Dorpat repeatedly defied other rulers of medieval Livonia.[45] After the decline of the Teutonic Order following its defeat in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, and the defeat of the Livonian Order in the Battle of Swienta on 1 September 1435, the Livonian Confederation Agreement was signed on 4 December 1435.[46]

Salient features

This culminated in the 24 February 1918 Estonian Declaration of Independence from the then warring Russian and German Empires. Democratic throughout most of the interwar period, Estonia declared neutrality at the outbreak of World War II, but the country was repeatedly contested, invaded and occupied, first by the Soviet Union in 1940, then by Nazi Germany in 1941, and was ultimately reoccupied in 1944 by, and annexed into, the USSR as an administrative subunit (Estonian SSR). Throughout the 1944–1991 Soviet occupation, Estonia's de jure state continuity was preserved by diplomatic representatives and the government-in-exile. Following the bloodless Estonian "Singing Revolution" of 1988–1990, the nation's de facto independence from the Soviet Union was restored on 20 August 1991.

Estonia is a developed country, with a high-income advanced economy, ranking very highly (31st out of 191) in the Human Development Index.[47] The sovereign state of Estonia is a democratic unitary parliamentary republic, administratively subdivided into 15 maakond (counties).

With a population of just about 1.4 million, it is one of the least populous members of the European Union, the Eurozone, the OECD, the Schengen Area, and NATO.

Estonia has consistently ranked highly in international rankings for quality of life,[48] education,[49] press freedom, digitalisation of public services[50][51] and the prevalence of technology companies.[52]

Theoderik of Estonia

Theodoric the Great (454–526), often referred to as Theodoric, was king of the Germanic Ostrogoths (475–526)[53] ruler of Italy (493–526), regent of the Visigoths (511–526), and a patricius of the Eastern Roman Empire. His Gothic name Þiudareiks translates into "people-king" or "ruler of the people".[54]

थिओडेरिक: ठाकुर देशराज

ठाकुर देशराज [55] ने लिखा है ... देवऋषि* - इनको यूनानियों ने थिओडेरिक नाम से याद किया है। इन्होंने 489 ईसवी में इटली के तत्कालीन बादशाह है ओडोवकर पर चढ़ाई की थी। 4 वर्ष तक लड़ाई चलती रही। अंत में बादशाह ने आधा राज्य जाटों को बांट दिया। थोड़े दिन बाद देवऋषि ने बादशाह को मरवा कर सारे इटली पर कब्जा कर लिया। इटली का बादशाह होते ही देवऋषि ने प्रजा सुधार के कार्य आरंभ कर दिए। बाग-बगीचे सड़क और नहर में नगरों की मरम्मत कराई। रोमन लोगों को ऊंची ऊंची नौकरियां दी। उनके राज्य से रोम की जनता इतनी खुश हुई कि यह कहती थी कि यह लोग पहले से ही क्यों न आ गए। 33 वर्ष के राज्यकाल में

* याद रहे कि इन लोगों के नामांकन में ऋषि शब्द रहने के कारण एशिया में यह लोग ऋषिक कहलाने लग गए थे।

[पृ.165]: देव ऋषि ने रोम को कुबेरपुरी बना दिया था। इतने अच्छे बहादुर और उदार राजा की 526 ई. में मृत्यु हो गई।

एस्टोनिया

एस्टोनिया, आधिकारिक तौर पर एस्टोनिया गणतंत्र उत्तरी यूरोप के बाल्टिक क्षेत्र में स्थित एक देश है। इसकी सीमाएं उत्तर में फिनलैंड खाड़ी, पश्चिम में बाल्टिक सागर, दक्षिण में लातविया और पूर्व में रूस से मिलती है। एस्टोनिया मौसमी समशीतोष्ण जलवायु से प्रभावित है।

एस्तोनियाई बाल्टिक फिन्स के वंशज है और फिनिश भाषा से एस्तोनियन भाषा में बहुत सी समानताएं हैं। एस्टोनिया का आधुनिक नाम रोमन इतिहासकार टेसीटस की सोच माना जाता है, जिन्होंने अपनी किताब जरमेनिया (Germania) (ca. ई. 98) में व्यक्ति का उल्लेख ऐसिती के रूप में किया।

एस्टोनिया एक लोकतांत्रिक संसदीय गणतंत्र है और पन्द्रह काउंटियों में विभाजित है। देश की राजधानी और सबसे बड़ा शहर तालिन्न है। केवल 1.4 करोड़ की आबादी के साथ, एस्टोनिया यूरोपीय संघ का सबसे कम की आबादी वाला सदस्य है। एस्टोनिया 22 सितम्बर 1921, से लीग ऑफ नेशन, 17 सितंबर 1991 से संयुक्त राष्ट्र, 1 मई 2004 के बाद से यूरोपीय संघ और और 29 मार्च 2004 के बाद से नाटो का सदस्य है। एस्टोनिया ने क्योटो प्रोटोकॉल पर भी हस्ताक्षर किए हैं।

References

- ↑ Matthew Holehouse Estonia discovers it's actually larger after finding 800 new islands The Telegraph, 28 August 2015

- ↑ Mägi, Marika (2018). In Austrvegr: The Role of the Eastern Baltic in Viking Age Communication across the Baltic Sea. BRILL. pp. 144–145. ISBN 9789004363816.

- ↑ Harrison, D. & Svensson, K. (2007). Vikingaliv. Fälth & Hässler, Värnamo. ISBN 91-27-35725-2

- ↑ Tvauri, Andres (2012). Laneman, Margot (ed.). The Migration Period, Pre-Viking Age, and Viking Age in Estonia. Tartu University Press. p. 31. ISBN 9789949199365. ISSN 1736-3810.

- ↑ Rätsep, Huno (2007). "Kui kaua me oleme olnud eestlased?" (PDF). Oma Keel (in Estonian). 14: 11.

- ↑ Tamm, Marek; Kaljundi, Linda; Jensen, Carsten Selch (2016). Crusading and Chronicle Writing on the Medieval Baltic Frontier: A Companion to the Chronicle of Henry of Livonia. Routledge. pp. 94–96. ISBN 9781317156796.

- ↑ "Country Profile – LegaCarta".

- ↑ Laurisaar, Riho (31 July 2004). "Arheoloogid lammutavad ajalooõpikute arusaamu" (in Estonian). Eesti Päevaleht.

- ↑ Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. p. 23. ISBN 9042008903.

- ↑ Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. p. 24. ISBN 9042008903.

- ↑ Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. p. 26. ISBN 9042008903.

- ↑ Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 4. ISBN 9780230364509.

- ↑ Laurisaar, Riho (31 July 2004). "Arheoloogid lammutavad ajalooõpikute arusaamu" (in Estonian). Eesti Päevaleht.

- ↑ Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 5. ISBN 9780230364509.

- ↑ Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. p. 28. ISBN 9042008903

- ↑ Frucht, Richard C. (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 68. ISBN 9781576078006.

- ↑ Tvauri, Andres (2012). The Migration Period, Pre-Viking Age, and Viking Age in Estonia. pp. 33, 34, 59, 60.

- ↑ Mäesalu, Ain (2012). "Could Kedipiv in East-Slavonic Chronicles be Keava hill fort?" (PDF). Estonian Journal of Archaeology. 1 (16supplser): 199. doi:10.3176/arch.2012.supv1.11.

- ↑ Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 9. ISBN 9780230364509.

- ↑ Raun, Toivo U. (2002). Estonia and the Estonians: Second Edition, Updated. Hoover Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780817928537.

- ↑ Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 9–11. ISBN 9780230364509.

- ↑ Enn Tarvel (2007). Sigtuna hukkumine Archived 11 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine Haridus, 2007 (7–8), pp. 38–41

- ↑ Tvauri, Andres (2012). The Migration Period, Pre-Viking Age, and Viking Age in Estonia. pp. 322–325.

- ↑ Mägi, Marika (2015). "Chapter 4. Bound for the Eastern Baltic: Trade and Centres AD 800–1200". In Barrett, James H.; Gibbon, Sarah Jane (eds.). Maritime Societies of the Viking and Medieval World. Maney Publishing. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-1-909662-79-7.

- ↑ Mägi, Marika (2015). "Chapter 4. Bound for the Eastern Baltic: Trade and Centres AD 800–1200". In Barrett, James H.; Gibbon, Sarah Jane (eds.). Maritime Societies of the Viking and Medieval World. Maney Publishing. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-1-909662-79-7.

- ↑ Mägi, Marika (2015). "Chapter 4. Bound for the Eastern Baltic: Trade and Centres AD 800–1200". In Barrett, James H.; Gibbon, Sarah Jane (eds.). Maritime Societies of the Viking and Medieval World. Maney Publishing. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-1-909662-79-7.

- ↑ Martens, Irmelin (2004). "Indigenous and imported Viking Age weapons in Norway – a problem with European implications" (PDF). Journal of Nordic Archaeological Science. 14: 132–135.

- ↑ Raun, Toivo U. (2002). Estonia and the Estonians: Second Edition, Updated. Hoover Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780817928537.

- ↑ Raukas, Anto (2002). Eesti entsüklopeedia 11: Eesti üld (in Estonian). Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus. p. 227. ISBN 9985701151.

- ↑ Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 7. ISBN 9780230364509.

- ↑ Laurisaar, Riho (29 April 2006). "Arheoloogid lammutavad ajalooõpikute arusaamu" (in Estonian). Eesti Päevaleht.

- ↑ Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Harvard University Press. p. 690. ISBN 9780674023871.

- ↑ Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 14. ISBN 9780230364509.

- ↑ Raukas, Anto (2002). Eesti entsüklopeedia 11: Eesti üld (in Estonian). Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus. p. 278. ISBN 9985701151.

- ↑ Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 15. ISBN 9780230364509.

- ↑ Raukas, Anto (2002). Eesti entsüklopeedia 11: Eesti üld (in Estonian). Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus. p. 279. ISBN 9985701151.

- ↑ Plakans, Andrejs (2011). A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 54. ISBN 9780521833721.

- ↑ O'Connor, Kevin (2006). Culture and Customs of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9780313331251

- ↑ Raun, Toivo U. (2002). Estonia and the Estonians: Second Edition, Updated. Hoover Press. p. 20. ISBN 9780817928537.

- ↑ O'Connor, Kevin (2006). Culture and Customs of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 10. ISBN 9780313331251.

- ↑ Pekomäe, Vello (1986). Estland genom tiderna (in Swedish). Stockholm: VÄLIS-EESTI & EMP. p. 319. ISBN 91-86116-47-9.

- ↑ Jokipii, Mauno (1992). Jokipii, Mauno (ed.). Baltisk kultur och historia (in Swedish). Bonniers. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9789134512078.

- ↑ Miljan, Toivo (2015). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 441. ISBN 9780810875135.

- ↑ Frucht, Richard C. (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 100. ISBN 9781576078006.

- ↑ Frost, Robert I. (2014). The Northern Wars: War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe, 1558 – 1721. Routledge. p. 305. ISBN 9781317898573.

- ↑ Raudkivi, Priit (2007). Vana-Liivimaa maapäev (in Estonian). Argo. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-9949-415-84-7.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2020: Estonia" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2020.

- ↑ "Estonia (Ranked 21st)". Legatum Prosperity Index 2020.

- ↑ "Pisa rankings: Why Estonian pupils shine in global tests". BBC News. 2 December 2019.

- ↑ "Estonia among top 3 in the UN e-Government Survey 2020". e-Estonia. 24 July 2020.

- ↑ Harold, Theresa (30 October 2017). "How A Former Soviet State Became One Of The World's Most Advanced Digital Nations". Alphr.

- ↑ "Number of start-ups per capita by country". 2020.stateofeuropeantech.com.

- ↑ Grun, Bernard (1991) [1946]. The Timetable of History (New Third Revised Edition ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0-671-74271-X.

- ↑ Langer, William Leonard (1968). "Italy, 489–554". An Encyclopedia of World History. Harrap. p. 159. "Thiudareiks (ruler of the people)"

- ↑ Thakur Deshraj: Jat Itihas (Utpatti Aur Gaurav Khand)/Parishisht,p.164-165

Back to Europe